Human Rights Situation in the Philippines

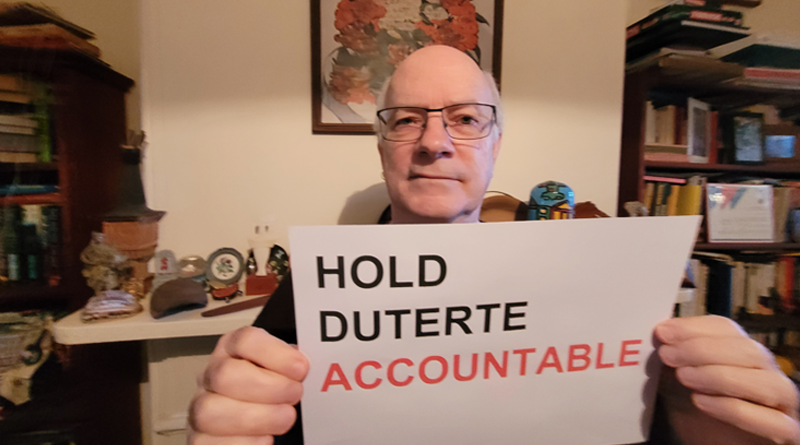

Interview with Mr. Peter Murphy, the Chairperson of the ICHRP

1. First of all, you have been working to promote human rights in the Philippines for a long time, and now you are the Chairperson of the ICHRP. Please provide a brief personal introduction and a description of what ICHRP is.

My name is Peter Murphy. I am a journalist and trade union member and activist, living in Sydney, Australia. I first visited the Philippines in 1981 as a seafarer on an Australian bulk carrier. Later in 1989 I was able to participate in an Asia-Pacific Peoples Conference on Peace and Development which was focused on the presence of the US military bases at Clark and Subic. This is where I met with the KMU Labor Center and on my return to Australia I became involved with the Philippines Australia Union Link. I have been doing that trade union liaison work ever since, and it is through that work that I because involved in the founding of the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines at a conference in Quezon City in 2013. Since 2016 I have been the Chairperson of the Global Council of ICHRP. It is composed of organizations outside the Philippines, to demonstrate the level of international concern at the very bad human rights situation in the Philippines. It aims to mobilize ever more democratic organizations around the world to try to call the governments of the Philippines to account for the serious violation of human rights taking place. The membership of ICHRP is strongly based in churches as well as trade unions and lawyers organizations.

2. Since Duterte came to power, many people have been killed in the name of the so-called war on drugs. Recently, there is also news that the ICC is also starting an investigation. Please outline the human rights situation in the Philippines.

You should note that the escalating extrajudicial killings of leaders of indigenous communities in Mindanao under the previous President, Benigno Aquino III, motivated the creation of ICHRP in 2013. There was a brief period in the second half of 2016 when President Duterte seemed to open the way for a de-escalation of these human rights violations, but at the same time he launched his war on poor people in Metro Manila and it soon became clear that he only had contempt for human rights and was promoting mass murder.

By the end of 2017, families of victims of this war on the poor had become organized through Rise Up for Rights and Life, exhausted the avenues of appeal against the extrajudicial killing of their relatives and had taken cases to the International Criminal Court. There were at least two groups of complaints to the ICC which were supplemented with extra evidence, mainly public incitement by President Duterte to kill alleged drug suspects. And by then there was a significant amount of media coverage, with photographs, of these murder scenes, and the number of cases was already considered to be well over 10,000. So in March 2018 the International Criminal Court began a preliminary examination of this material, with the aim of deciding whether it should put its own investigators onto the task of assembling evidence. Duterte immediately announced that the Philippines would withdraw from its recognition of the ICC, which became effective on March 19, 2019. The war on poor people in the guise of a war on drugs continued and escalated, spreading to urban areas outside Metro Manila. By now the estimated body count is over 30,000. It didn’t stop during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns from March 2020 either.

The longstanding pattern of extrajudicial killing of political activists on the left in the Philippines also took a pause in the nine months of Duterte’s presidency as he pursued peace talks with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, and there were ceasefires in the countryside. But then the attempt to arrest Isnilon Hapilon, who claimed to be a leader of Islamic State in the region, in Marawi City in May 2017 triggered heavy fighting in the city. President Duterte declared Martial Law in all of Mindanao, and decided against any negotiated de-escalation of the conflict, instead opting for a heavy artillery and aerial bombardment of the city. This was a huge violation of the human rights of the Maranao people in Marawi City, over 1000 civilians were killed and over 400,000 were displaced. Even today there are over 120,000 still displaced.

By the end of 2017, President Duterte had terminated the peace talks with the NDFP, declared the Communist Party and the New Peoples Army to be terrorists, and started arresting and killing the NDFP Peace Consultants, who are unarmed civilians and also specifically provided with immunity from arrest and security guarantees.

The island of Negros became the laboratory for deadly repression of the civilian left with over 40 executed and hundreds arrested in a series of security operations from December 2017 through until today. This killing machine was then established nation-wide from the end of 2018 with the creation of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict. The task force is led by military and police generals who can call on all government departments and agencies to join in the repression. The murderous system was applied on the Tumandok indigenous leaders in Panay on December 30, 2020. Nine were executed and 17 arrested. They were opposing a South Korean mega dam project on their ancestral lands. Then on March 7, 2021, the same method was used in the industrial provinces south of Manila, when 9 leaders were executed and another six arrested.

Altogether, since Duterte came to power up to March 31, 2021, there were 394 cases of extrajudicial killing of civilian left political activists, according to the Karapatan Alliance for Human Rights. Of these 313 were peasants, 60 were workers, teacher or government employees, and of the total 14 were minors and 57 were women.

3. When the Duterte administration took off, there was support from the majority of the people. In fact, the promises he made in the early days of the regime raised expectations for a new society for those who fought for human rights and democracy in the Philippines. But why do you think Duterte has gone on a path of radical conservatism and returned to a violent rule?

In hindsight, President Duterte only made big promises to peasants and workers to win the 2016 elections. But at the time, because the Benigno Aquino III presidency was such a disappointment, a huge majority of Filipino voters believed in Duterte’s promises. But he has broken his promise of land to the peasants, a national minimum wage and an end to contractualization to the workers. He promised peace talks, and in the end reversed into a total war on the left.

But during Duterte’s long period as mayor of Davao City he operated death squads against the poor. So his election promise to fill Manila Bay with the corpses of drug peddlers was no exaggeration. Duterte in his character is a ruthless killer and misogynist. Not only does he talk like a street thug, but he is one.

However, this is not enough of an explanation for the behaviour of an entire government. Duterte’s initial economic program was a nasty neoliberal formula to increase taxes on the poor and cut taxes on the rich, to enable speculative investment in urban development projects that would displace millions of urban poor. His government borrowed big for projects that would benefit elite families and foreign investors. In this Duterte was maintaining and extending the policies of his predecessor. Despite his horrible street thug behaviour, he is in fact a traditional politician, like his father was in the Marcos government.

After the Marawi siege, Duterte’s government massively boosted spending on the military and police, and on the president’s own discretionary funds. Despite some fracas with the US government over a visa for his favourite police chief, Duterte consolidated relations with the US and its military after the Marawi siege. During the pandemic lockdown, the government provided cash support for three months to a significant number of those affected, but then cut it off while the lockdown extended for another 16 months. During the pandemic Duterte cut social welfare massively.

Overall the Duterte government has been the worst in decades for job creation and for adjustments to the minimum wage.

4. Next year there will be a presidential election in the Philippines. With the current constitution of the Philippines, which adopts a six-year single term, Duterte cannot become president again. So there is news that Duterte is running for vice president and his daughter is running for president. Is this possible in the Philippines, which has a long tradition of popular movement? What caused these unusual things to happen?

Duterte has announced that he will run for Vice-President for his PDP-Laban Party, and it is not yet clear that his daughter Sara will be the Presidential candidate, but we should expect that. Dynastic politics is entrenched in the Philippines so it is almost normal for a daughter or a son to be the candidate for a position which a parent can no longer contest under the Constitution. Since a Vice-President would replace a President who dies or resigns, Duterte’s move could lead to a breach of the Constitution which is very clear that a person can only ever have one six-year term as President. There is likely to be a court challenge once Duterte lodges his nomination, and this will be a test of the independence of the Supreme Court, which has been very compliant to Duterte.

Why is this happening? Duterte wants to protect himself and his children from any prosecution for his actions as President. The rule of law is entirely optional in Duterte’s Philippines, and this is yet another demonstration of the President’s contempt for any idea that he is accountable for his actions.

5. Various international solidarity activities have been conducted to improve the human rights situation in the Philippines. What kind of tasks do you think should be done for more effective international solidarity activities in the future? In particular, if there is anything that civil society in Korea can do, what would it be?

The South Korean government provides military equipment to the Philippines, and its official overseas aid is supporting destructive projects like the Jalaur Mega-Dam project on Panay, for which Daewoo Construction has the contract. Civil society in South Korea could become educated about these aspects of relations between the two countries and then put pressure on the South Korean government to suspend or cancel these programs until the human rights situation in the Philippines is corrected.

As well, there are many Filipino overseas contract workers in South Korea. Church and trade union organizations in South Korea could develop their connection with these OFWs, who have their own progressive organizations. This is a very good way to build solidarity, to help uphold the rights of these OFWs, and to also shield them from threats of repression from the NTF-ELCAC.

South Korean organizations can join ICHRP and thus strengthen the international level of solidarity with the Filipino people as they struggle to assert their basic collective and individual rights.