For “Bonn, Kathen and Tean” in Our Daily Lives

Cha Mikyung

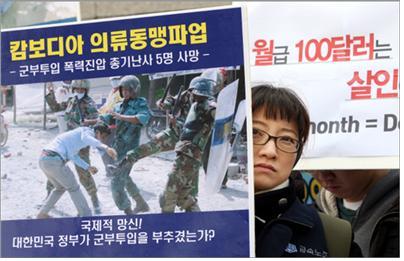

In January 2014, the demand for a minimum wage hike made by garment workers at an industrial complex near the Cambodian city of Phnom Penh turned into a political protest. As hundreds of thousands of people began to protest, the armed soldiers emerged, killing some workers and injuring thousands of them. At that time, I happened to be visiting Battambang and Siem Reap, so I could hear from my friend about the socio-cultural background of why the protest had turned into an anti-government struggle. The protest was reminiscent of the violence and soldiers that their parent’s generation had experienced.

www.hani.co.kr

Cambodia is a traditional agricultural country with a large population of farmers, with more than 70% of the population working in the primary industry (agricultural, fishing, and forest industries). Most are children of farmers. The farmers in Cambodia are victims, survivors and parties of genocide by the Khmer Rouge regime. The death-toll during the Khmer Rouge regime between 1975-1979 occurring through torture, execution and forced labor is still unclear. It is, depending on the literature, estimated to be between 1 million and 2.2 million, or one-fourth to one-fifth of the whole population. Reflective study and documentation of the tragedy and of the cause of the Cambodian genocide continue today.

The Toul Sleng (S-21) prison and the Choeung Ek mass grave have been transformed into a Toul Sleng Massacre Museum and opened to the public, but when I first went there, it was dismal and shabby. Only a few of the 20,000 inmates in this prison, which was originally a high school site, have survived. The skulls on display remind me of the failure of modern times and the failure of reason left behind by the Nazi genocide.

David Chandler, author of S-21, writes in details in his book “Voices from S-21” that the incident was clearly a part of the history of terrorism. Terrorism is the most intense planned social disaster of all disasters.

Some historians like William Shawcross argue that the U.S. indiscriminate massacre of nearby Cambodian farms in 1970 when seeking to attack the stronghold of the South Vietnam Liberation Front, later provided the cause for many farmers to join the Khmer Rouge Communist Party. Even so, the barbarism and madness shown by the powers and soldiers of the Pol Pot regime, which cannot be explained only by communist ideals and delusions, is an event that shows how violent humans can be.

http://www.killingfieldsmuseum.com

It is important to clearly understand the challenges and limitations of the politician Sihanouk in Cambodia’s modern history with Pol Pot, the main culprit of the massacre. Since the independence of Cambodia, which was a French colony in 1953, Sihanouk has contributed to the country’s neutrality by declaring a boycott of the military alliance at the Geneva conference in 1954 and promulgating the Permanent Neutralization Act in 1957. In 1955, he participated in the Bandung Conference of Indonesia as a member and actively led the Asia-Africa non-alignment movement. But the image of a failed politician he showed clearly tells us that frustration is easier than change in daily life without citizens and democracy. The neutralization line and Bandung spirit he had pursued in his early politics were eventually thrust aside and the historical memories of this era were locked up in a forgotten space amid the capital-led globalization order.

Afro-Asia Conference in Bandung, 1955 (ANTARM/IPPHOS)

Cambodia, with diverse cultures and races, is a country where Khmer people, who have long believed in Hinayana Buddhism, account for more than 90 percent of the population. Due to globalization, the physical distance of Asians who have different races, languages, and cultures has narrowed more than ever. The poverty-stricken reality highlighted by the garment workers is only one example. Among the 48,000 Cambodian people living in Korea, the hardships faced by workers in farming and fishing villages and marriage immigrants are also a reality for the people, and the current discourse on globalization cannot solve them. The socio-economic difficulties, the democracyi crisis, and the internal pain left over from the massacre still continue today in Cambodia. I believe that solidarity between us Koreans and Cambodians is only possible when we seriously consider the way in which we remember our pain and stay together with each other.

I still remember the poster produced by a community group in Siem Reap, “Don’t use children for your relief efforts.” Solnit Rebekah, who studied disasters, noted the phenomenon of “pauperization” which makes independent people dependent and has a tendency of putting individual interests ahead of public interests.

Now, Cambodia will have to constantly reflect on where and how changes, problems of self-reliance, daily horizontal relationships and freedom will be possible amid the influx of the charity industry and development of NGOs and religious projects from all over the world including Korea.

Chin Ya-han, a Cambodian, stresses the spirit of the “Bonn, Kathen, Tean” to build daily peace from the spirit, culture and experience of coexistence they have traditionally kept. The beginning of peace seen by Ya-han begins with the place of life where hospitality is extended to one another. A village or region is not distinguished by age, gender, status, host or guest. Preparing a meeting for hospitality is the beginning of healing. Boundaries are eased among those who share this practice without discrimination, caring for the needy and maintaining solidarity. Sincere invitations are delivered to the people, and those invited gather to pray for someone, dance their traditional dances and share food. In prayer, material sharing and blessing, we ask someone for forgiveness and express joy in new encounters.

Solnit noted that disasters are ruins, but through sincere care and friendship, human nature becomes a space of exploration in which the year of jubilee is celebrated amid this pain.

For Kathen, everything that is barely alive,

For Bonn, in which anger and confusion are eliminated,

For Tean, a gift for each other to be helpful and dedicated.

The old tradition of “‘Bonn, Kathen, Tean” can be a gift of peace for those who have lived through a terrible disaster, so I tell them that I want to join Bonn Katen Tean.

“For you and me!”